West Somerset used to be home to multiple orchards. Every village had them. The fruit was regarded as very important hence the age old practice of ‘wassailing’ the trees to ensure the next year’s crop would be bountiful. Carhampton is the village which has continued this practice for decades though some villages like Dunster and Porlock have now reinstated the custom.

Apple Day is another annual feature on the Carhampton calendar which I have attended every year for the past 20 years. You can get apples identified there as well as buy a wide variety of English apples, apple chutneys and apple cakes. You can also get your apples juiced there or buy juice made from the village’s community orchard apples. All great fun.

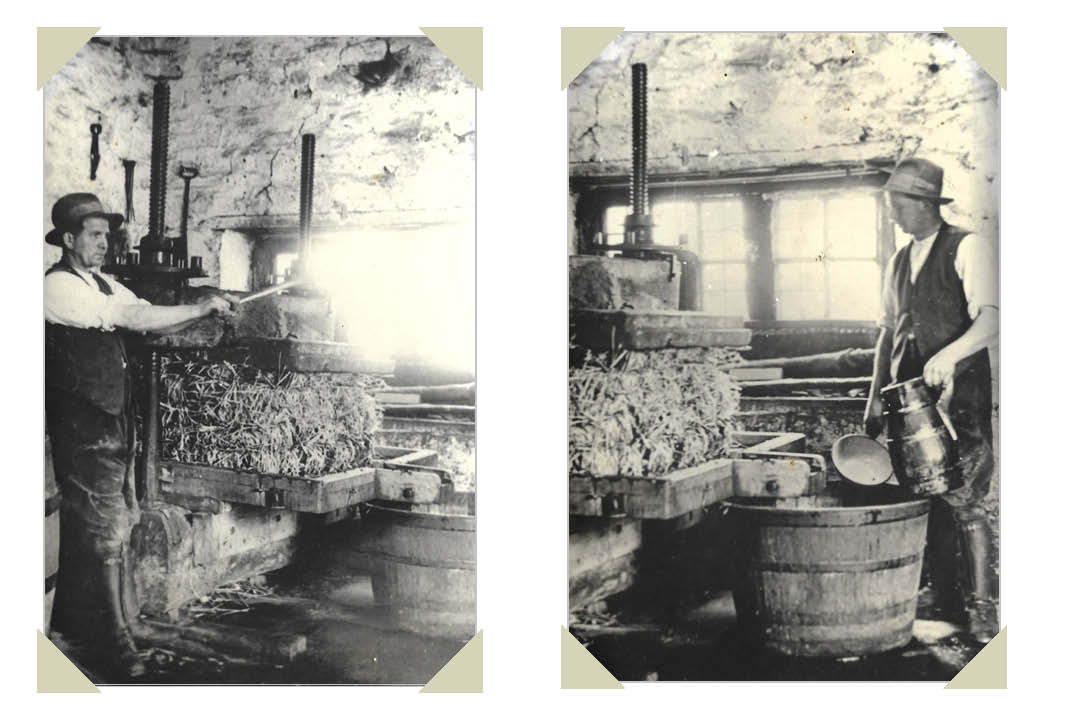

Somerset, along with Kent and Hampshire, were historically the three principal cider producing counties. It has been famed for good scrumpy for 100s of years using the traditional method of making with a sharper type of cider apple. Cider was traditionally seen as a health supplement beneficial to the skin as well as being an enjoyable alcoholic drink. This led to a proliferation of cider mills.

Sheppy’s has been producing cider for over 200yrs and Thatchers has been making it at Myrtle Farm since 1904. They both still use their own apple orchards to brew their cider. The UK drinks more than any other country in the world although its popularity has fluctuated. There was a time when it was drunk at breakfast! Then it took a back-seat to imported wines and ports but is once more enjoying a resurgence.

Between the C16 and C17s the world experienced a period of cooling. This drop in temperature killed off grapes in Britain but apples survived so cider became the leading beverage. Then during the Napoleonic Wars 1792 – 1815 British farmers were pressurized to produce grain and livestock to ensure domestic supply so cider orchards were neglected.

The first orchards in Somerset appear to have been planted by clerics and religious orders. Many people in the SW believed cider had a religious significance and it was not unusual for babies to be christened with cider until the C15. Bishop Beckingham is recorded as having planted ‘a most beautiful orchard with divers fruits’ at Banwell whilst there in the 1400s and Bishop Selwood of Glastonbury planted an orchard of over 3 acres of apple and pears trees around 1475. These orchards seem to have been pleasure grounds like the one associated with Orchard Wyndham, which belonged to Cleeve Abbey until 1287.

Maps and surveys of West Somerset show that every estate and small holding had an orchard. A survey taken in the mid 1700s shows this to have been true in Carhampton and map of 1827 show the centre of the village as a mass of apple trees. Woodcombe too was dominated by orchards.

The first written record of cider as payment dates back to 1204 to a manor house in Norfolk. For centuries wealthy landowners paid their farm labourers up to 8 pints a day.

Some visitors travelling by stagecoach to Minehead in the 1800’s were told by the driver that a labourer’s wage was 12s, rent for his cottage 1s –1s 6d. A quart of cider supplemented his wages which if given in too great a quantities rendered the man unsteady on his feet! I found this extract from ‘The ‘Romance’ of the Peasant Life’ written by Francis George Heath in 1872:

“One great difficulty with the peasants in Somersetshire is what is called ‘the cider question’. This county being one of the finest cider-producing ones in England, the system prevails of giving the labourers daily, in small kegs or firkins,a certain quantity of cider, seldom less, I believe, than 3 pints a day. I obtained the testimony from an old man, who had been a farm labourer for 50yrs who gave me a truthful description of the horrible liquor that was given to the agricultural labourer under the ironical name of cider.

It is a well known fact that a farmer nearly always keeps ‘two taps running’, one for himself and his friends and one tap for farm labourers. The farmer’s own cider- I can speak from my own knowledge – is most carefully made. The very best apples are selected and the manufacturing process is carefully gone through, and real cider produced. If a stranger to the county wants to taste the cider, the farmer will give him what he tells him in confidence that he keeps ‘for his own drinking ‘. Now the labourer’s cider is tap number 2. The very worst apples are, in the first place , selected – the windfalls; and these with dirt and slugs are ground up for the peasants.

When the windfalls are used for feeding the pigs, the labourer has what is called the ‘second wringing’ – that is to say the apples from the farmer’s own drinking cider are put into the press and after the best part of the juice has been extracted , the cider ‘cheese’, as the mass of apple in the press is called, is subjected to yet greater pressure and what is expressed from the ‘cheese’ on this occasion is called the ‘second wringing’.

This is greatly inferior to the ‘first wringing’. To complete the process and make a liquor worthy of tap number 2 , the following plan is adopted:- To every hogshead of the ‘second wringing’ is added 4 gallons of hop-water. This is added for the purpose of preserving the ‘second wringing’, which without such addition would from its thinness and inferiority turn into vinegar.

My informant, to give me some idea of the difference in quality between the two taps said that the good cider usually costs about 30s, whilst the ‘second wringing’ was worth only 10s a hogshead.

There is no doubt that the cider system is a very bad one. It would be infinitely better that the peasant should be given the value of the cider which, bye the bye, is generally estimated by the farmer to be worth considerably more than it is really worth, in money. To a man with such wretched wages every penny is of value. But the system is unfair to the labourer because under the ‘cider system’ his wages are greatly over-estimated; and I believe the horrible compound which farmers call cider, but which I think should properly be called vinegar, works the most pernicious effect upon the constitution of the rural labourer.

Francis Heath born 1843 in Totnes and educated in Taunton was a writer, conservationist and supported the open spaces movement.

A campaign to stop payment in the form of alcoholic beverages brought about the addition of a clause to the Truck Act 1887 which prohibited wages in this way. In 1901 a group of farmers in Worcester appealed against The Truck Act prohibiting the use of cider as wages but its use gradually died out.

“I’ll never get Scrumpy here” sang the Wurzels.

Oh yez you will!! Cheers.

Compiled by Sally Bainbridge on behalf of Minehead Conservation Society.

Buy the book! Minehead & Beyond

This book is a compilation of articles written for this magazine by Sally Bainbridge on behalf of Minehead Conservation Society. It contains information about the richness of West Somerset’s history; culture; people; heritage; traditions and beautiful and varied landscape. The book costs just Es and all profits go to Minehead Conservation Society.

Available to buy from AR Computing, Park Lane Home Furnishing (in their Park Lane shop), Minehead Tourist Information Centre and Townsend House (Monday am).

Office: Townsend House, Townsend Road, Minehead TA24 5RG (01643 706258) E-mail: [email protected]